Water Faucets

Welcome

Hello, and thanks for checking out this site! I’ve been thinking about making a website/blog for a while, but at this stage of the internet it feels a little difficult to get started. After all, there are so many great blogs and websites that have been at it for five or ten years - what could I possibly contribute?

In his autobiography, Richard Feynman describes a time when he was starting to lose touch with his love of physics after the loss of his wife and his experience on the Manhattan Project. He also describes how he broke out of it:

Physics disgusts me a little bit now, but I used to enjoy doing physics. Why did I enjoy it? I used to play with it. I used to do whatever I felt like doing - it didn’t have to do with whether it was important for the development of nuclear physics, but whether it was interesting and amusing for me to play with. When I was in high school, I’d see water running out of a faucet growing narrower, and wonder if I could figure out what determines that curve. I found out it was rather easy to do. I didn’t have to do it; it wasn’t important for the future of science; somebody else had already done it. That didn’t make any difference: I used to invent things and play with things for my own entertainment.

So I got this new attitude. Now that I am burned out and I’ll never accomplish anything, I’ve got this nice position at the university teaching classes which I rather enjoy, and just like I read the Arabian Nights for pleasure, I’m going to play with physics, whenever I want to, without worrying about any importance whatsoever.

Within a week I was in the cafeteria and some guy, fooling around, throws a plate in the air. As the plate went up in the air I saw it wobble, and I noticed the red medallion of Cornell on the plate going around. It was pretty obvious that the medallion went around faster than the wobbling.

I had nothing to do, so I start to figure out the motion of the rotating plate. I discover that when the angle is very slight, the medallion rotates twice as fast as the wobble rate-two to one. It came out of a complicated equation! Then I thought, “Is there some way I can see in a more fundamental way, by looking at the forces or the dynamics, why it’s two to one?”

I don’t remember how I did it, but I ultimately worked out what the motion of the mass particles is, and how all the accelerations balance to make it come out two to one.

I still remember going to Hans Bethe and saying, “Hey, Hans! I noticed something interesting. Here the plate goes around so, and the reason it’s two to one is…” and I showed him the accelerations.

He says, “Feynman, that’s pretty interesting, but what’s the importance of it? Why are you doing it?”

“Ha!” I say. “There’s no importance whatsoever. I’m just doing it for the fun of it.” His reaction didn’t discourage me; I had made up my mind I was going to enjoy physics and do whatever I liked.

I went on to work out equations of wobbles. Then I thought about how electron orbits start to move in relativity. Then there’s the Dirac Equation in electrodynamics. And then quantum electrodynamics, QED. And before I knew it (it was a very short time) I was “playing” - working, really - with the same old problems that I loved so much, that I had stopped working on when I went to Los Alamos: my thesis-type problems, all those old-fashioned, wonderful things.

It was effortless. It was easy to play with these things. It was like uncorking a bottle: Everything flowed out effortlessly. I almost tried to resist it! There was no importance to what I was doing, but ultimately there was: The diagrams and the whole business that I got the Nobel Prize for came from that piddling around with the wobbling plate.

– Richard Feynman, Classic Feynman

I first read Classic Feynman about ten years ago, when I was working in a machine shop but considering going back to school for physics. At the time, what stuck with me was the realization that I would have no idea how to model water falling out of a faucet, which was apparently a no-brainer for Feynman in high school. Actually, I forgot all about the wobbling plate until today, when I went back to look up that quote.

Anyway, I think his story is about learning to keep asking questions like “How does that work?” or “Can I make that?” Or, more broadly, it’s about making space to keep doing what you love, even if you find that bureaucracy and administrative overhead are starting to intrude on your dream job. And how making sure that you still love doing it can lead to surprising results.

Not that I would describe myself as burned out. But all that to say, I’m starting a blog at what might be the busiest time in my life because I’m hoping it will encourage me to continue making and learning new things. Against my natural inclinations, I’m also doing it in public view because I’m hoping it will push me to actually stick with it and avoid the embarrassment of a blog with only one post. In other words, this is basically for an audience of one, but maybe somebody else somewhere will get something out of it as well.

Since it’s on my mind and I’ve never actually worked it out before, I might as well start with Feynman’s water faucet model. This will need a little basic physics, but no calculus or particular fluid mechanics expertise.

The water faucet problem

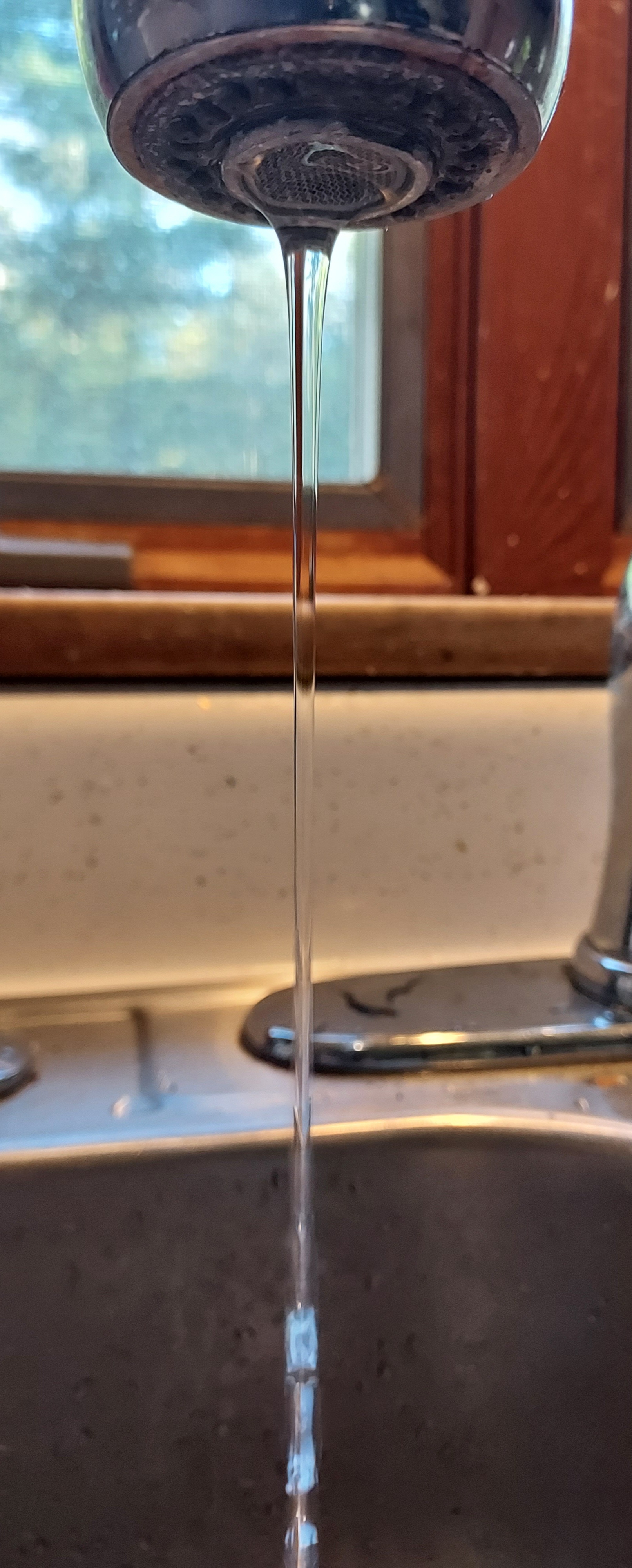

Let’s say we crack open the sink faucet and see something like this:

How could we model the width of the stream as a function of its height? Before starting a model, there are a few things to notice here:

- The water stream is basically steady near the faucet (meaning that the stream itself doesn’t move, not that the water doesn’t move)

- After a while the stream becomes unsteady and breaks up into droplets

- The initial stream is basically laminar

We can also make a couple of modeling assumptions that will make things much easier. First, assume the water is an “ideal fluid”, meaning that it is inviscid, incompressible, and we can ignore surface tension. All three of these are technically wrong, but it’s actually a pretty reasonable place to start. Later we could go back and think about how wrong each of these actually is. If the water is an ideal fluid then the steady, laminar part of the flow can be modeled using the principles of conservation of mass and energy applied to fluid flow. I’ll also assume that the velocity profile at the faucet is uniform and that the pressure throughout the free flow (once it leaves the faucet) is constant and equal to atmospheric pressure.

Conservation of mass

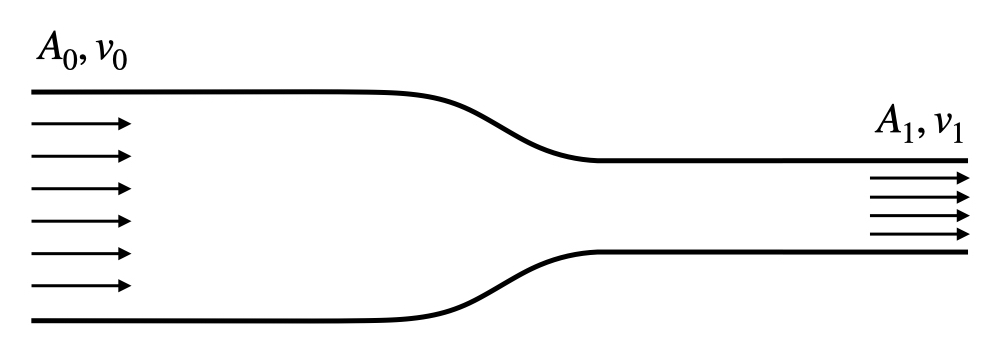

In classical mechanics, conservation of mass is the simple statement that mass can neither be created nor destroyed. How does that apply to a moving fluid? Let’s say we have a pipe whose cross-sectional area steps down from $A_0$ to $A_1$, and assume that all the water in the pipe is moving with a uniform constant horizontal velocity of $v_0$ when the pipe has area $A_0$, and $v_1$ when the pipe has area $A_1$:

If the fluid is incompressible and has constant density $\rho$, the mass in any fixed volume is constant in time. If we take the volume between the two points shown in the figure, this means that the mass flowing into this volume in any given time must be exactly equal to the mass flowing out. In some time interval $\Delta t$, the mass that flows into this volume is $\rho A_0 v_0 \Delta t,$ and likewise for the outflow. Dividing out the arbitrary time interval and the constant density, mass conservation then says that $A_0 v_0 = A_1 v_1$.

This approach of selecting a convenient volume and applying the conservation laws is called the control volume method. Actually, this expression for $v_1$ is more general. It works as long as no fluid is entering or leaving the volume through the side walls. It works if the inflow and outflow velocities aren’t uniform as long as we use the average velocities. It even works if the velocities aren’t totally horizontal, but we just have to take the component of velocity that is perpendicular to the inflow and outflow surfaces (since this is the only part of the velocity that carries mass in or out of the volume).

Conservation of energy

The relevant form of conservation of energy for an ideal fluid is called Bernoulli’s equation. It’s not as easy to derive as the application of conservation of mass, so I’ll skip it here and just try to argue that it makes intuitive sense, but there are plenty of good resources on it out there.

Bernoulli’s equation states that for an ideal fluid with density $\rho$, velocity $v$, pressure $p$ and height $h$ (in the direction opposite gravity $g$)

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{2} \rho v^2 + \rho g h + p = \mathrm{constant} \end{equation}

along streamlines of the flow. A “streamline” for steady flow is exactly what it sounds like: the line that you’d see if you injected dye into some point of the flow. Bernoulli’s equation allows any of the variables $\rho$, $v$, $p$, and $h$ to vary along streamlines, as long as this particular combination remains constant.

The easiest way to interpret this is as a statement of energy per unit volume. In standard Newtonian mechanics, a mass $m$ moving at speed $v$ would have kinetic energy $(1/2) m v^2$ and potential energy $mgh$. So if we look at an infinitesimally small blob of fluid, we basically just replace mass $m$ with density $\rho$ to get $(1/2) \rho v^2$ and $\rho g h$.

To me, the pressure term makes more sense if we apply Bernoulli’s equation at two points along a streamline:

\begin{gather} \frac{1}{2} \rho v_0^2 + \rho g h_0 + p_0 = \frac{1}{2} \rho v_1^2 + \rho g h_1 + p_1 \end{gather}

Rearranging, this is really saying that $\Delta \mathrm{KE} + \Delta \mathrm{PE} = -\Delta p$. This now feels more like a standard energy conservation statement, which suggests the interpretation that $\Delta p$ corresponds to work done by our infinitesimal blob of fluid on the surrounding fluid in between points 0 and 1.

Modeling the faucet flow

Let’s say the faucet has radius $R$ and the initial flow is uniform with vertical velocity $v_0$. Since the height coordinates are arbitrary and the only thing that matters is the relative height, let $h_0=H$ be the height of the water faucet. If we trace a blob of water along its streamline to some lower point $h_1$ we can apply Bernoulli’s equation:

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{2} \rho v_0^2 + \rho g H + p_0 = \frac{1}{2} \rho v_1^2 + \rho g h_1 + p_1. \end{equation}

Again, assuming this free flow is at atmospheric pressure, $p_0 = p_1 = p_\mathrm{atm}$. Then Bernoulli’s equation simplifies to

\begin{equation} \frac{1}{2} v_0^2 + g H = \frac{1}{2} v_1^2 - g h_1, \end{equation}

which gives the velocity $v_1$ as a function of the known faucet velocity $v_0$ and the relative height $\Delta h = H - h_1$.

Next, we can apply mass conservation using the control volume of the water column between the faucet and height $h_1$:

\begin{equation} v_0 (\pi R^2) = v_1 (\pi r^2), \end{equation}

where $r$ is the radius of the water column at a distance $\Delta h$ below the faucet. Finally, combining this with Bernoulli’s equation,

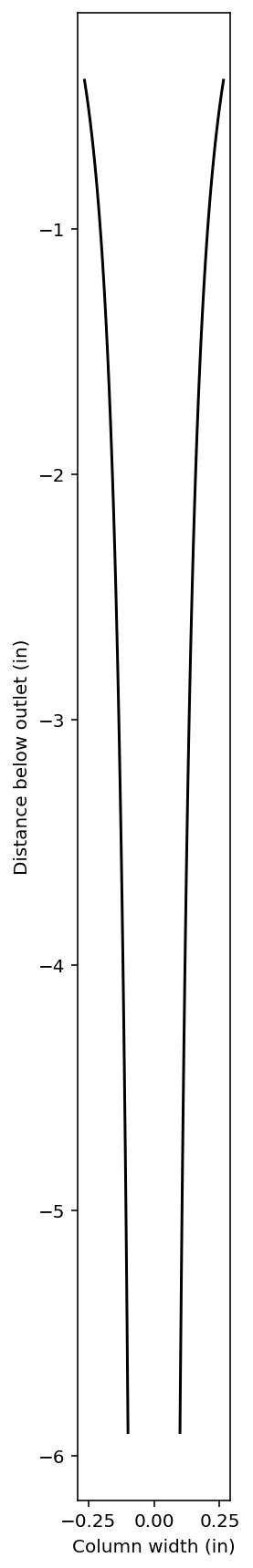

\begin{equation} r(\Delta h) = \sqrt{ \frac{v_0 R^2}{\sqrt{v_0^2 + 2 g \Delta h}} } \end{equation}

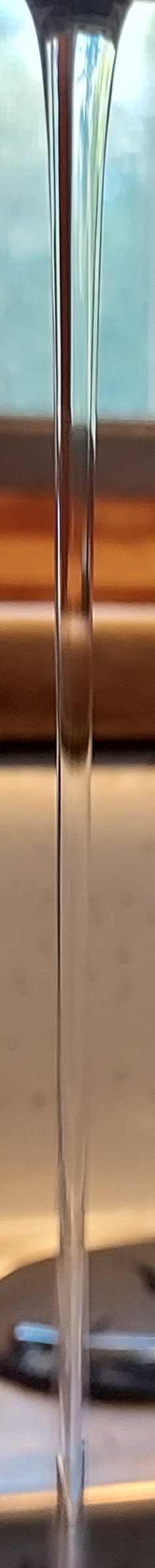

| Kitchen sink | Model |

|---|---|

|

|

Not bad! But there’s one big factor this model doesn’t account for: the breakdown of the stream. Once the water column gets, say, six inches below the faucet it loses this nice laminar profile and breaks down into… what? Turbulence?

Instability and droplet formation

Not exactly. It turns out that the breakdown of the stream into droplets is a manifestation of a hydrodynamic instability mode called a Rayleigh instability. Generally speaking, hydrodynamic stability is a branch of fluid dynamics that models the effect of disturbances to steady flows like the one we just derived. If the disturbances are small, you can linearize the unsteady equations of motion (using an extension of the Taylor series from Calculus 101) and determine whether the disturbances tend to grow or decay in time.

The reason for doing this is that nature is full of disturbances. So if the flow in stable (meaning that all possible small disturbances are damped), then this is the flow you tend to see in reality. On the other hand, if the flow is unstable (meaning that at least one particular disturbance tends to be amplified), then sooner or later that mode will be randomly excited and the steady flow will tend to break down into some other form. In the case of the faucet flow the instability is a result of surface tension and there is some point where droplets have less surface area than the water column. Then the flow becomes unstable to a particular wavelength of perturbations, which grow until droplets start to pinch off.